Alvarado pulls some pitches from his past as he looks to the future

I recently got an e-mail informing me that a watch company was reissuing a long out of production model from 1982. An analog-digital dual watch, with all sorts of wonderfully outdated features, like an alarm built right in. For some reason I felt this odd pull to it, with its awkward part-digital face tickling some sort of nostalgic corner of my brain. I wasn’t even born until 1993. I’m not alone in this sort of (in my case, faux-) nostalgia, I suspect. Sales on vinyl records have skyrocketed in recent years. American tourists in Japan scour shelves of secondhand electronics shops in search of video game consoles that would’ve been considered outdated 20 years ago. There’s some wonderful and often inexplicable pull to the things of the past, even if they were a little clunky at the time. Maybe that explains José Alvarado’s recent pitch additions.

In the TGP state of the bullpen preview, I wrote that Alvarado was adding a 4-seam fastball and a curveball for the 2025 season. That wasn’t quite correct, though. He’s re-adding them. When Alvarado started his major-league career in Tampa Bay, he used a four-pitch mix, with the 4-seamer and curveball alongside his now-familiar cutter and sinker. But, like the dinosaur, dodo, and Carolina parakeet, the 4-seam and curve went extinct. Or almost extinct; from 2019 to present, both have popped up a few times a year, usually occupying the “did he throw that or did Statcast get confused” zone. Years after putting those particular playthings back in the toybox, Alvarado is bringing them back, hoping they’ll prove the key to a bounceback season. But if the 4-seamer and curveball have the potential to help him, why’d he put them away in the first place?

The 4-seamer was Alvarado’s most frequent offering in his debut season of 2017, at 39.4%. It was a solid pitch, with batters posting a .231 average and .346 slugging percentage against it. It didn’t induce a lot of whiffs compared to his other offerings, but it was effective enough. Just one season later, though, it was all but gone: he threw just 14 in 2018. Nothing about the pitch was notably bad, nothing about it made it stand out as being in egregious need of replacement. But it was replaced nonetheless. The likely cause wasn’t what the 4-seamer was, but rather what it wasn’t. Alvarado’s sinker was a boom or bust pitch in 2017; it induced a lot of whiffs (28.2%), but it also got hit a lot (BA .355 against), and hit hard (.452 slugging percentage against). Still, Tampa Bay’s staff saw something in it (the peripherals suggested a much better pitch than the actual results had shown), and liked the idea of making it a bigger part of his arsenal. In 2018 the sinker became his primary pitch, offered 69.2% of the time versus 36.4% a year prior. That increase in usage came largely at the 4-seamer’s expense. The 4-seamer wasn’t bad, but it didn’t offer the upside that the sinker did. Alvarado had a killer season with the sinker, and the 4-seamer became yesterday’s news.

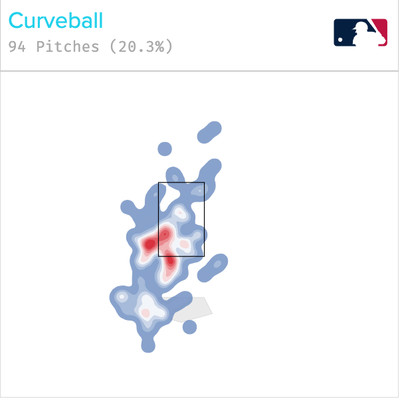

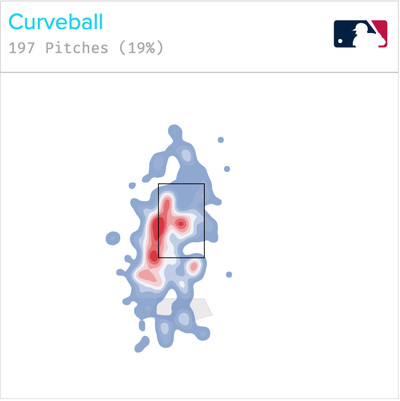

The curveball was also a common sight at first: in 2017, Alvarado had it at 20.3% usage. He largely maintained that usage in 2018, then nearly abandoned it in 2019, throwing just 22 of them. At first, it’s hard to see why he left it behind. In 2017 batters posted identical batting averages and slugging percentages of .038 against it. It generated whiffs at a 51.6% clip that year. In 2018 the pitch had a downturn… to the effect of a .113 BA/.151 slugging against, with 39.3% being whiffed at. When a pitch can perform substantially worse year-over-year and still produce numbers like that, why on earth would you want to stop throwing it?

These charts may shed some light on the situation:

When Alvarado threw the curveball, it went all over the place. The heat map can only be described as ameboid; if you’ve ever seen those science-class videos of white blood cells chasing down and engulfing bacteria, it looks a little like that. It was a great pitch when it went where he wanted it to go; it just didn’t go there with enough consistency. If it had been the only pitch he struggled to locate, he could have devoted more time to it and perhaps found a fix. But Alvarado struggled with his command across all of his pitches, and the Tampa Bay coaching staff clearly thought that focusing on his cutter and sinker was the more promising path. The curveball, while never entirely disappearing, was clearly deemphasized.

Alvarado came over to the Phillies via trade following the 2020 season, and pitching coach Caleb Cotham, assessing the arsenal of his new weapon, decided that the curveball was a problem. The delivery he used to throw it was distinct from the one he used for his other pitches, and Cotham felt that it was getting in the way of Alvarado developing a clean, consistent feel for his slider and curveball delivery, like radio interference cutting into a song. Cotham counseled Alvarado to focus on the sinker and cutter, and he did so (although he still threw a curve every now and then in 2022). Alvarado planned to bring the curveball back as a bigger part of his gameplan in 2023, with a new grip and delivery meant to cut down on the interference issue. But despite feeling optimistic about it in spring training, Alvarado never threw the curve in a regular season game. His sinker-cutter game was never better than in 2023; perhaps there was simply no need to mix in anything else. You throw what you’ve got until batters prove they can hit it, and they never got around to doing that with the 2023 versions of Alvarado’s slider and cutter.

But they did get around to it in 2024, hence the return of Alvarado’s old friends. Everything old is new again. There is nothing new under the sun. History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. Pick your cliché. But note that José Alvarado is not the same pitcher in 2025 as he was in 2017. His old mix might bring about new results.