Bohm might want to try a rabbit’s foot.

There’s a goat at Citizens Bank Park. Not in the literal sense, as the denizens of Wrigleyville had to deal with (no curse of the Philly goat, please), and not in the acronymous sense either. Per the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, goat is “a derisive name for a player who is singled out for a serious lapse in performance” (you almost certainly already know the meaning; I just wanted an excuse to pull the baseball dictionary off my shelf). Right now, the goat of the Phillies is Alec Bohm, struggling to a .158/.172/.175 line to start his 2025 campaign. Meanwhile, Bryson Stott’s .250/.321/.375 line has done enough to excuse him from the daily slings and arrows coming from the more disgruntled members of the Phlock (although he has, to use parlance that you won’t find in the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, caught some strays as a result of general dissatisfaction with the Daycare).

Numbers, of course, never lie. The slash lines clearly show that Bohm has been an absolute mess to start the season, whereas Stott, while not setting the world on fire at the plate, is keeping his head above water. But there’s also lies, damned lies, and statistics. Or rather, lies, damned lies, and the use of the wrong statistics. If you look in the right place, the stories of Bohm and Stott flip.

In addition to logging what we actually see on the field, the baseball world keeps track of what we should expect to see, based on the underlying qualities of pitches and swings. Each ball that’s put in play has its exit velocity and launch angle measured, which allows it to be compared to other balls that were put in play with similar metrics. And that, in turn, allows for the calculation of how often we would expect a batted ball to become a hit, as well as what we would expect a player’s batting statistics to be based only on the characteristics of the balls they put in play.

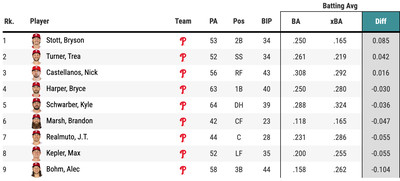

Here’s all the qualified batters for the Phillies, sorted by the difference between their actual batting average and their expected batting average:

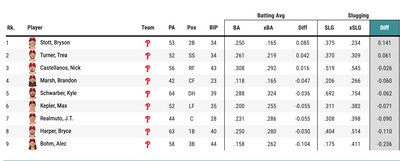

And here’s the difference between their actual and expected slugging percentage:

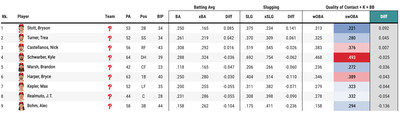

And the difference between their actual and expected weighted On-Base Average:

There’s a clear story here: through the early goings, Stott has been by far the luckiest of the Phillie batters, and Bohm has been by far, the unluckiest. So much so that one has to wonder if Bohm might have broken a mirror, or forgotten to toss salt over his shoulder. Or perhaps his recent haircut sapped his powers, as if he were a modern-day Samson.

Follicular tragedies aside, let’s start with Stott. He’s one of three qualified Phils, along with Trea Turner and Nick Castellanos, to have an actual batting average higher than his expected. The difference between the two for Stott is .085, twice as high as Turner’s 0.42. Similarly, the same trio are the only Phillies to have a positive difference between actual and expected wOBA, and Stott and Turner are the only two Phillies to have a positive difference between actual and expected slugging percentage. Stott’s observed statistics are neither exceptionally bad nor exceptionally good, but his expected statistics are near the very bottom of the league: 5th percentile xWOBA, 4th percentile xBA, 5th percentile xSLG.

And looking at the other Baseball Savant sliders, it’s easy to see why: he swings the bat slow, doesn’t barrel the ball with great frequency, and as such has posted among the lowest average exit velocities and hard-hit rates in the league. In fairness, Stott has always brought a slow stick to the plate, finding his success not with power but with a general refusal to whiff and a strong ability to square-up his swings, getting the most out of them. The difference in 2025 is that he’s not squaring-up right now. In 2023, he squared-up 33% of his swings, putting him in the 95th percentile across MLB. In 2024, he squared-up 30.2% of his swings, putting him in the 87th percentile.

In 2025, he’s squaring-up 17.2% of his swings, putting him in the 11th percentile. You can find some success swinging the bat slowly if you make good contact. You shouldn’t be able to find success swinging the bat slowly and not making good contact. So far in 2025, Stott has. But there’s every reason to believe that’s the result of some good luck. His BABIP of .333 is not likely to be sustainable. Of all MLB players, only José Altuve is outperforming his expected xwOBA by more than Stott. It’s safe to say that Stott probably can’t get the results he’s had while taking swings like this for long.

Bohm is on the other end of the luck spectrum. He’s far from alone in having observed statistics that lag behind his expected for all 3 of BA, SLG, and wOBA; most of the Phillies do. But he can still claim to be unusually unlucky. The second biggest gap between actual and expected BA belongs to Max Kepler, with a -.055. Bohm’s gap is nearly twice as big. The second biggest gap between actual and expected for SLG and wOBA belong to J.T. Realmuto at -.09 and -.054; Bohm’s gaps are over twice those. If Bohm’s expected numbers were his actual numbers, he’d be hitting for a .262 average and a .411 SLG. Not phenomenal numbers, but certainly enough to ward off the worst of the criticisms that have been facing him.

Looking under the hood, Bohm is making good contact, squaring-up 35.3% of his swings (94th percentile). 54.5% of the time he hits the ball, he hits it hard (86th percentile), and his average exit velocity is in the 89th percentile. He’s chasing too much and barely working any free passes, but the underlying metrics suggest that Bohm isn’t batting terribly. He’s had bad luck, to the tune of a .205 BABIP. It would likely be overly reductive to suggest that Bohm’s issues are purely out of his control, nothing more than happenstance. He has had extended downturns before, which perhaps suggests that he might be prone to them for whatever reason. But only 1 player (Andrew Vaughn) is underperforming his xwOBA by more than Bohm. There’s no doubt that his struggles aren’t properly reflective of the approach he’s taking at the plate.

Suggesting that Bohm and Stott will swap places as the seasons go on— that Bohm will surge, and Stott will crumble— would be too simple. For one thing, small sample size is impacting their numbers, for another, they’ll both certainly make some adjustments as the season goes on, and for a third, luck, good or ill, can persist to some degree over the course of a full season. But it is likely that Bohm cannot go on being this unlucky, and that Stott cannot go on being this lucky across a whole campaign.

But Bohm might want to grow his hair back out, just in case there is something to the Samson thing.